United States of America

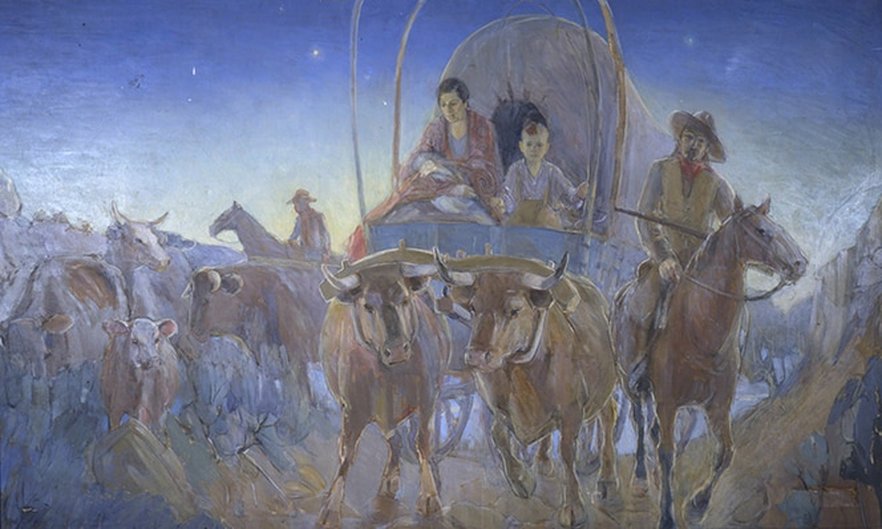

Nobody knew it then, but the genetic mutation came to Utah by wagon with the Hinman family. Lyman Hinman found the Mormon faith in 1840. Amid a surge of religious fervor, he persuaded his wife, Aurelia, and five children to abandon their 21-room Massachusetts house in search of Zion. They went first to Nauvoo, Illinois, where the faith’s prophet and founder, Joseph Smith, was holding forth—until Smith was murdered by a mob and his followers were run out of town. They kept going west and west until there were no towns to be run out of. Food was scarce. They boiled elk horns.The children’s mouths erupted in sores from scurvy. Aurelia lost all her teeth. But they survived. And so did the mutation.

Earlier this year, I met Gregg Johnson, Lyman and Aurelia’s great-great-great-great grandson. The genetic mutation that had traveled the Mormon Trail was now in Gregg, one of hundreds of the Hinmans’ descendants in the Utah area. Gregg is 61, with blue eyes and a white goatee. He frequently travels for his job as a craftsman for Mormon temples, but Utah is still home. “I’m just a Salt Lake City boy,” he says.

The mutation that came with the Hinmans turns out to be a troublesome one. It lies dormant just long enough for people to have children and pass the mutation along, but not long enough to watch their children start their own lives. Gregg’s mother died of colon cancer at age 47. Her mother also died early of colon cancer, as did her mother. And who knows how many other relatives succumbed, stretching all the way back when the Hinmans came to Utah.

Gregg knows the history of this mutation in a gene called APC because he’s spent more than 30 years in a series of studies at the University of Utah—made possible by a vast trove of Mormon genealogy records. Detailed family trees make it easier to trace genes that cause disease. After the Hinmans and other pioneers settled in the state, the Mormon church kept records that over time became an unusually detailed and complete genealogy. In the 1970s, university researchers had the foresight to combine these genealogy records with the state cancer registry to create what ultimately became the Utah Population Database. So when scientists began suspecting a genetic cause for cancer, they went hunting through the Mormon family trees.

They found patterns of deadly inheritance: BRCA1, one of the infamous cancer mutations, as well as mutations for cardiac arrhythmia and melanoma. And of course, they found the APC mutation behind the colon cancer in Gregg’s family. Utah became an accidental genetics laboratory. When Lyman hitched his wagon for Utah a century and a half ago, he ended up setting a course for colon cancer research.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or the Mormon church, has one of the largest genealogy databases in the world. Today, it operates a family-history library just steps from the temple in downtown Salt Lake City, where banks of computers await visitors interested in digital genealogy records. The Church has physical records, too. They are stored on microfilm under 700 feet of rock in the climate-controlled Granite Mountain Records Vault, secured with doors so heavy they’re supposed to withstand a nuclear blast. Mormons are, by stereotype, family oriented, and this intense interest in family trees is a matter of theology.

Read the rest of the story at The Atlantic

The Atlantic

Latest posts by The Atlantic (see all)

- Groundbreaking Ceremony Held for Jacksonville Florida Temple - January 25, 2026

- Missionaries honored with Community Impact Award - January 23, 2026

- Church of Jesus Christ meet with Palau President to strengthen humanitarian efforts - January 21, 2026

- Timeless Servants of Faith - January 21, 2026